Beyond Bars

Established in 1989, the AKC CGC program teaches dogs and people how to behave and be more considerate of fellow citizens. After meeting once a week for 10 weeks, the human-dog pair is tested and receives CGC certification. CGC was not originally intended for condemned dogs and prison inmates. But one day in 2002, Dr. Mary Burch, who directs the CGC program, received an e-mail from Dorothy Miner, a dog trainer who volunteers at Allen Correctional Center in Lima, Ohio. Miner was working with prisoners to train shelter dogs and thought her training could be more effective with CGC techniques. Dr. Burch recognized the possibilities immediately. "I was so excited. These dogs are unadoptable — unattractive dogs no one wants. But the dogs could get adopted with the CGC training and certification."

Lindy Goetz is a trainer for Mixed Up Mutts, in LaPorte, Indiana, where for 10 years she has taken dogs from animal shelters and trained them for adoption, therapy work, and CGC training. One day in 2004, the managers of Mixed Up Mutts told Goetz they wanted her to do prison trainings. She knew all about the principles of canine good citizenship, but Goetz had never worked in a prison before. She vividly remembers walking into Westville Correctional Center, a medium-security prison in Westville, Indiana. Facing her students the first day, she recalls, "I stood and looked around at all of them, thinking, 'What did I just get myself into?' I wondered what all these guys did to end up in there. What in the world am I going to teach them?"

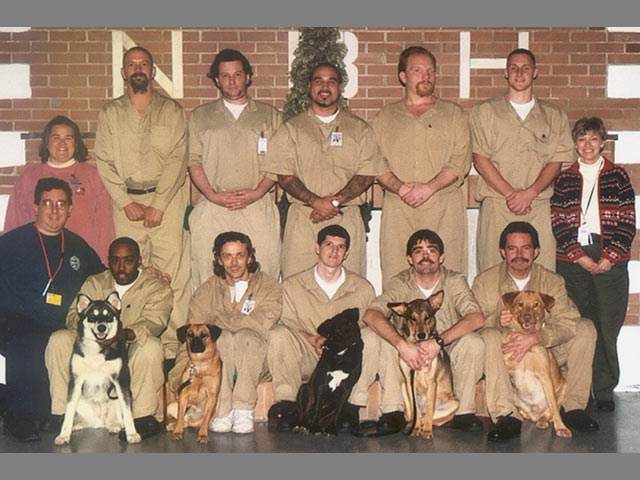

A natural trainer, Goetz figured out what to do. "Somewhere in myself, I knew this was a good idea, so I jumped in and started," she says. "Now all my fears are gone." Goetz, like the other trainers, works as a volunteer, driving 150 miles each way between her home and the prison. "At first, I told them not to expect me to be a major part of this. But then I fell in love with the program." Goetz now has a formal relationship with the prison, dubbed "Prison Tails."

Sharon Hawk is the complex director for Westville Correctional Center. Hawk was not a dog person and knew nothing about CGC. So when Mixed Up Mutts proposed the idea for a prison CGC program, she was doubtful. "This is the largest prison in Indiana. I just couldn't fathom bringing dogs in here." But she always looks for innovative programs, so she gave it a try.

* * *

The opportunity to change his life came the day Steven Kelty, an inmate at Westville, responded to an announcement for a dog-training job on the prison bulletin board. "I had worked in a kennel when I was in high school. So I kind of knew what they expected. I thought it would be neat getting into something like that."

Neil Cortner saw the same announcement. "I grew up with dogs all my life. I thought it would be fun to see what I could do. It sounded like I could learn something new, so when I get out I can do something better than selling drugs."

Both Cortner and Kelty went through an extensive screening, done by Ms. Hawk. "We look at their offenses," she says, "their institutional conduct, education level, and their overall behavior. We don't take any child molesters, sex offenders, or anyone with a record of domestic abuse." Hawk explains that domestic abuse is often about control and domination, which could be directed against the animals. Hawk looks for signs of underused intellect, a desire to work hard, and potential for compassion.

Once accepted, prisoners see the dogs they must work with. These are not your first choice for a pet. Sandy Laing is president of Angels for Animals, a shelter in Lima, Ohio, that provides dogs to Allen Correctional Center. Laing sees lots of what she calls "easy dogs," the ones whose eyes and cuteness beg you to take them home. "But the prisons get the dogs that have been chained outside their whole lives," she says, "or females that were used for breeding and never had any socialization. These dogs are not friendly." Puppies are generally more adoptable, but not the little terrors Laing sends to the prison. "These puppies have really bad problems. People had them for six months, then decided they can't take it any more, and they end up here."

In just 10 weeks things must turn around, or it's back to the kitchen for the inmate, and an even darker fate for the dog.

In twice-weekly classes, prisoners must absorb lessons in obedience, and show the trainers that they have mastered lessons from the previous week. Between classes, prisoners are required to keep a daily body-language journal with minute details about their dogs. Goetz cites some examples: "When is the dog's head lowered? What are the dog's eyes and ears like in different situations? Is the dog standing rigid, and is the tail up or down? Report the position of the eyebrows. And what was the situation — was someone walking by, was a bird on the other side of the fence?"

Prisoners also keep a daily-goals journal. Goetz says, "They write everything they are supposed to achieve that day. Did they reach their goal? If not, what are they doing differently to improve?" Goetz spends about six hours each week responding to the journals. "I'll go back to a prisoner and say, 'You wrote that your dog is afraid of this person, but you don't say why. Tell me what the person did. Was the person hovering over the dog or staring the dog in the eye?' I tell them to observe these things next time it happens."

Throughout the training, prisoners must attend to their dog's basic care and necessities. Kelty says, "A lot of guys hear about this program and think, oh yeah, that's a cool job. Then they get into it and find out how much there is. Suddenly they're saying, 'I don't know if I want to do this any more.' It doesn't take long to realize the responsibilities you have, and you've got to do all of them."

Diane Laratta, a CGC trainer at Allen Correctional Center, never misses a chance for a good life lesson. "One of the guys came to me one day and said, 'How do I stop a dog from pissing in my cell?'" She put the day's heeling lesson on hold to give a refresher course on verbal communication. "I told him, 'When you get out, you're going to go on job interviews, and language like that will turn people off.' I told him he needs to start using the right language now so he doesn't fall into that way of speaking later on."

Laratta invites veterinarians, groomers, and trainers to talk to the men about professional options. "You should hear the kinds of questions prisoners ask. They want to know how to earn certifications needed for these jobs." Never missing an opportunity for more learning, Laratta describes how one prisoner wanted to become a handler, but he never smiled. "I told him he's going into a service industry. 'You have to smile, whether you're feeling good that day or not. You need to present yourself as someone who's pleasant to be around.'"

Prisoners are constantly reminded that their goal is to get the dogs adopted. The CGC training becomes a daily practice in thinking of other people. Cortner and Kelty agree that thinking beyond themselves is the program's most fulfilling part. "After the dog goes into a new home," Cortner says, "we hear how the family thinks we did a great job training the dog. That's such a good feeling." Kelty agrees, adding, "It's such a great feeling looking back, knowing the dog needed all that training. But you get the dog adopted, and then you hear how the dog is doing. It makes you feel like you can do something in this world besides get in trouble."

* * *

When the training is done, Laing gets the dogs back at Angels for Animals, to try a second time to adopt them. She is often amazed at a dog's complete personality makeover, especially those she once described as "completely unadoptable, way too much energy, running in several directions at once." But when the dogs come back from prison, she says, "They're not just better behaved, there's a whole new demeanor. They have a thinking process they didn't have before. You can see the wheels turning."

Miner says, "We see lots of dogs with nothing going for them. People walk right by at the shelter." She remembers one dog like this. "He was on the verge of being put down for extreme hyperactivity. The dog was even starting to self-mutilate. The family that had the dog was in way over their heads and gave him to a shelter. But after the training he was rolling over and giving you his paw. People at the shelter would stop and say, 'Hey, look at this guy!'"

* * *

After 10 weeks, the training is done. There is a graduation ceremony, then the dog and the prisoner are separated. Prisoners are not allowed to have any contact with the adopting families, so it is truly good-bye. Miner says prisoners are quiet about it, but "It must be difficult for them, especially when they worked with a dog that had so many problems. During the graduation, you see them constantly petting the dog and the dog is wagging her tail."

Cortner has done several graduations. Being an experienced trainer seems to make him more comfortable revealing his emotions. "Every graduation brings tears to my eyes. But I want the dogs to have a second chance at life once they're out of here, just like I'll get one day."

* * *

Kelty's CGC efforts go far deeper than dog training. "It trains you to deal with people and difficult situations and conflicts. It teaches you communication skills you never knew you had. I've trained so many dogs, now the other guys come to me when they're having trouble. I don't just train dogs, I train other handlers."

Cortner has been completely changed by dog training, which was apparent during his 2005 hearing. The judge asked, "What will you do when you get out of prison?" Unlike other hearings, Cortner had a response. "Before I came into this program," Cortner told the judge, "I wouldn't know. But now I know I'm going to pursue grooming. I'm going to work with dogs. It can be working at a pet store or anywhere like that. But I'm going to do something along those lines." Cortner describes the judge's response: "He said, 'Mr. Cortner, you're not the same man that came in here 18 months ago not knowing what you want to do with your life. You've changed your life and I see that.' Well, I owe that to this program."

For families looking for a new pet, Miner says, "Let me tell you, the dogs that pass their CGC tests in prison are great dogs. The environment is so much more difficult than anything in regular CGC testing. There are tons of distractions and stresses. There are lots people in very close quarters. The dogs live in cells. You're in the middle of a test when the loudspeaker goes off. It's tough!"

According to Hawk, "Prisons are kind of an enigma to people in society. But they aren't just places of punishment. This program is teaching prisoners about responsibility, how to work hard and think of someone besides themselves. Everybody wins." This is from someone who once doubted whether the idea would work at all. "The dogs win, because someone trains them and makes them adoptable. And when the offenders get out, they have skills. This program is helping to prevent future crimes. And it all happens for free, because it's run by volunteers. But our society gets to see the benefits."